Building Resilient and Connected Communities

On November 30th, 2021, the Community Climate Action team hosted the second “built environment” focused workshop, featuring climate adaptation and resiliency building strategies and practices for high-rise communities, like St. James Town (SJT) and stakeholder members.

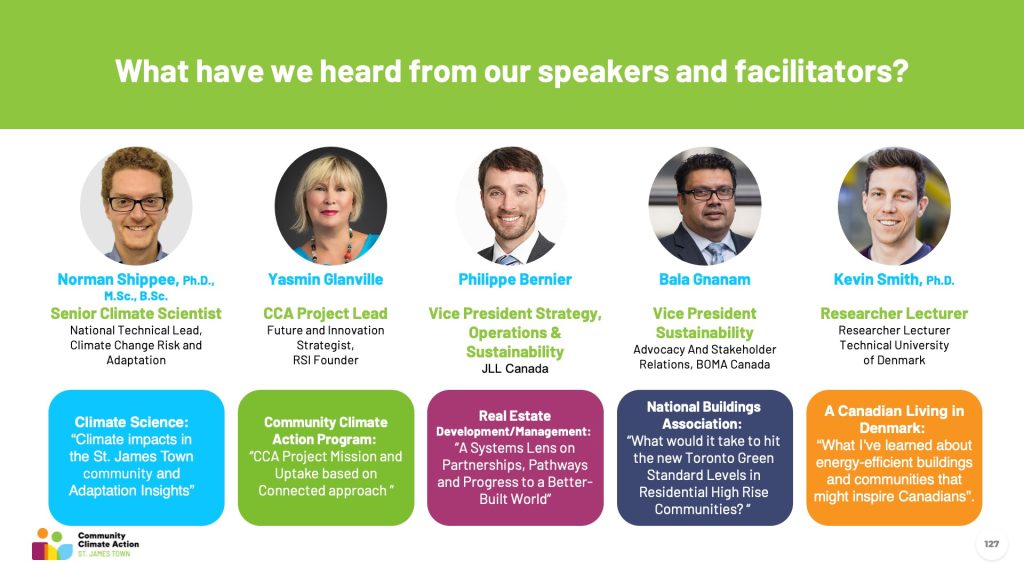

The workshop was facilitated by Stantec’s Senior Climate Scientist, Dr. Norman Shippee and the CCA-SJT project lead and RSI Founder, Yasmin Glanville. The speakers and participants from North America and Europe reflected a diverse representation of SJT commercial and residential tenants, building developer-owner and manager stakeholders, and leading science, energy and Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) experts. Learn more about the first building workshop.

Connecting the Dots for Context

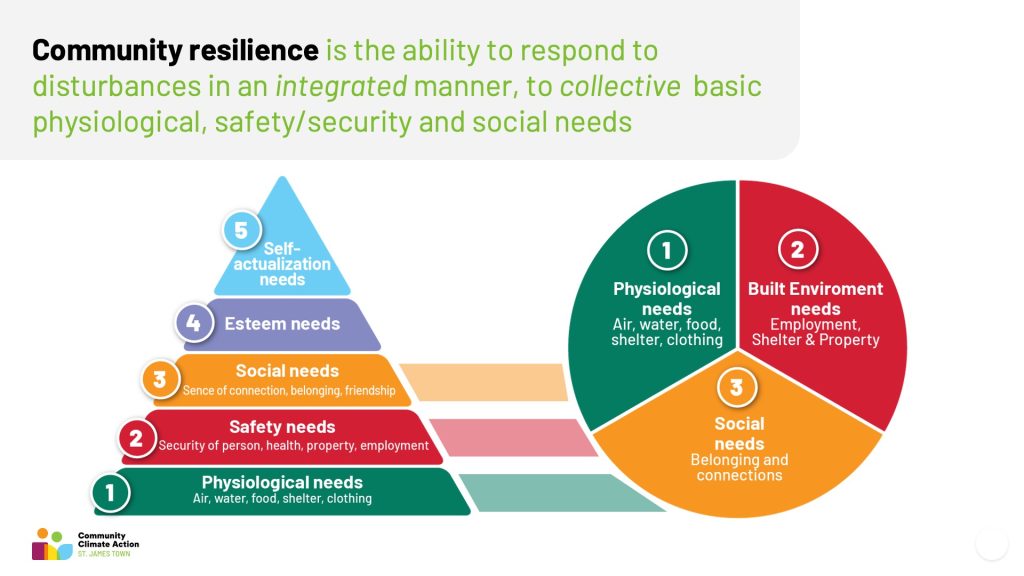

RSI-CCA’s approach to climate solutions for communities like St. James Town is focused on the essential needs of the people who live and work there: community members and stakeholders. One of these needs is to improve the climate resiliency of the community’s nineteen multi-residential rental towers. Most of them were built in the 1960s and 70s and are in dire need of upgrading to meet the City of Toronto’s green standards and targets under the City’s climate strategy known as “Transform Toronto”.

Toronto adopted “Tower Renewal” as a goal for retrofitting and upgrading the SJT towers about 10 years ago. The concept was initially promoted by ERA architect, Graeme Stewart. As recently as February 2020, the Urban Land Institute (New York) and the City of Toronto sponsored an inquiry into the towers. A recommendation to consider the towers as assets and prioritize the retrofits was made. However, the Covid-19 pandemic refocused City employees to the fight against the virus and, the Tower Renewal recommendations were put on pause.

Our Multi-Stakeholder and Inclusive Approach

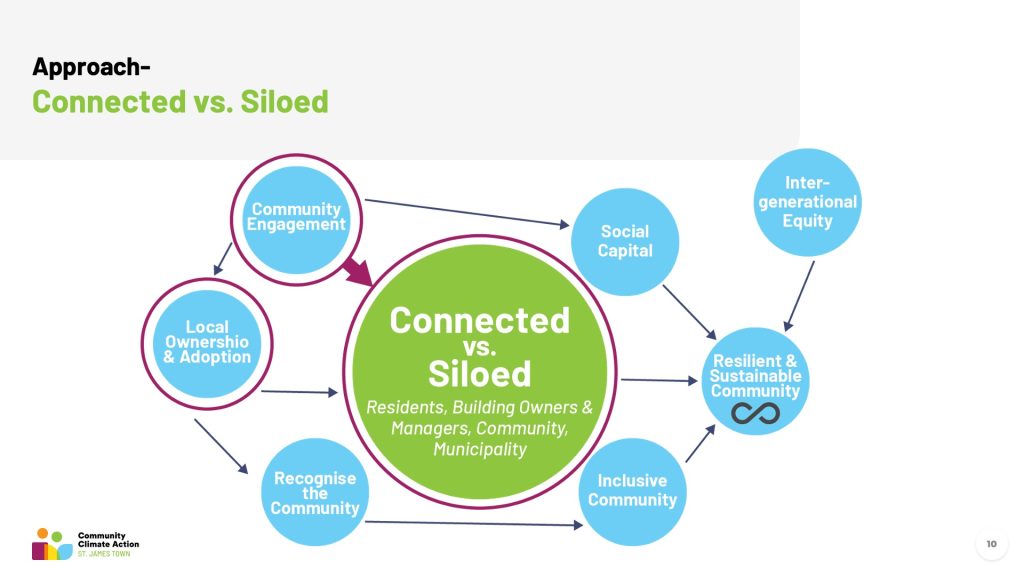

Given the pivot to online communications and the temporary pause on planned building retrofits in SJT, we adopted a systems approach to engaging a diverse group of commercial and multi-residential building stakeholders. The goal was to accelerate our understanding of what is being done to improve building performance as an important aspect of what’s being done inside and outside of Canada that can be applied to advancing the climate resiliency and future preparedness of SJT and other high-rise communities.

On November 30, 2021 CCA hosted a workshop to explore the holistic approach, solutions and strategies used by communities worldwide to improve building performance as an important part of addressing climate change and improving community resilience.

Yasmin Glanville, CCA-SJT Project Lead, introduced the session and goals: to look for solutions and options for future building preparedness, increase capacity, skills, resiliency, and the ability to respond with a collective approach. Keys to progress include: building social capital, players taking local ownership and engagement at the community level. We need to look beyond what is considered “normal”. Since March, the CCA-SJT group has been building a roadmap. It has trained 18 climate change Ambassadors and worked on projects aimed at improving physical building resiliency, food challenges, better deploying the labour force and more. In addition to training, mentorship programs and expert presentations on practical help for getting attention, buy-in and funding have helped move things forward.

Speaker Highlights

Facilitators & Speakers:

Expert Panelists:

Norman Shippee, Ph.D., Senior Climate Scientist

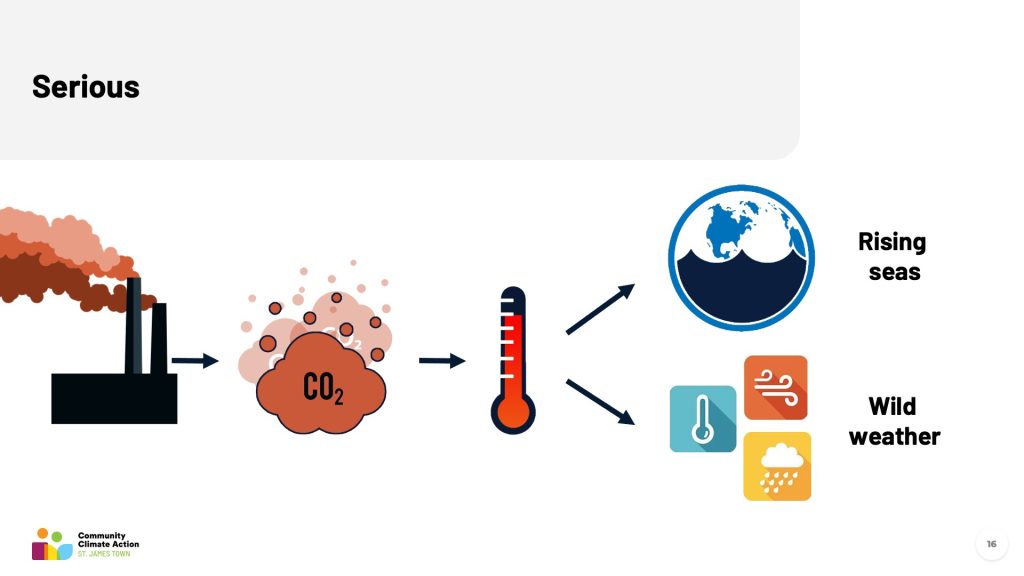

Norman recapped what he had spoken about at the September 23rd event. He talked about historic CO2 levels and 20 years of data that show climate change and how a lot of older infrastructure is not suitable to the impacts of wild weather and the direction climate change is taking us: citing ventilation, drainage systems, etc. The impacts on SJT include heat island effects and the strain of window-mounted A/C units on the electrical system. He reminded attendees about the cascading impacts of heatwaves on older buildings and their residents.

Norman outlined the elements of moving forward: identifying local leadership, thoroughly assessing resilience and setting goals, implementing and monitoring solutions for progress. This involves multiple stakeholders and is a major investment. The return on investment has gone from 4:1 to 12:1 over time.

Philippe Bernier, VP Strategy, Operations & Sustainability

JLL Canada

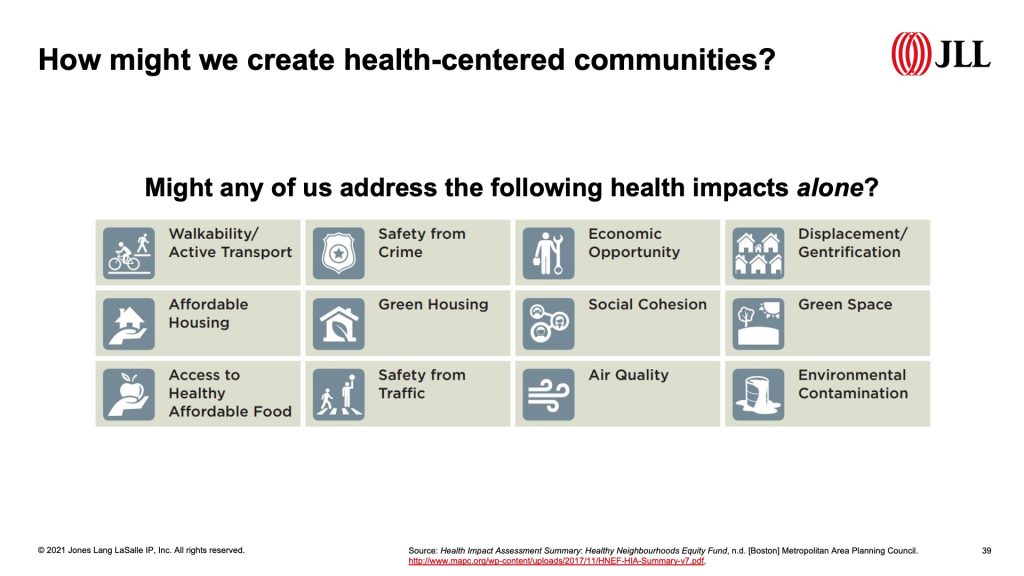

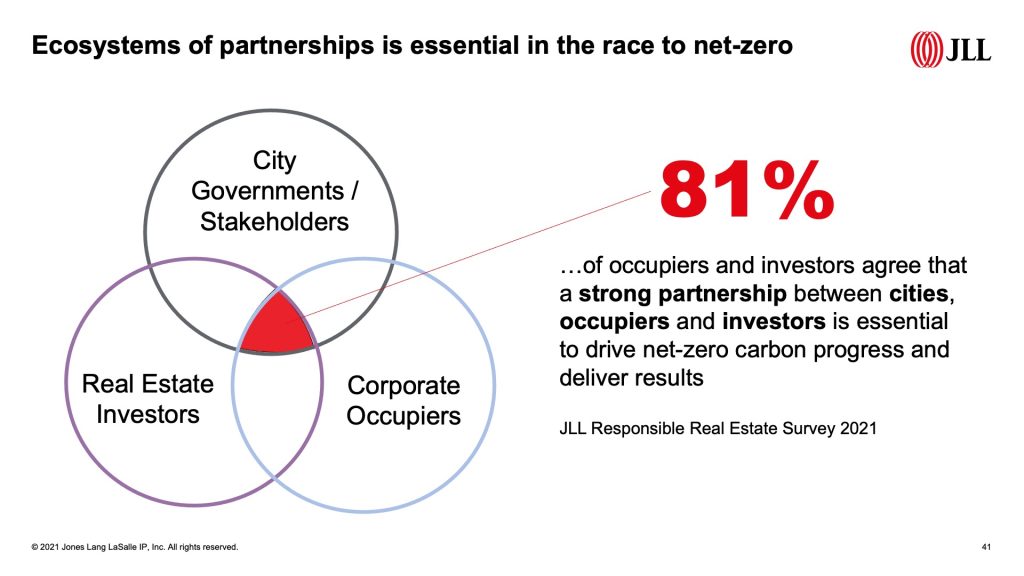

He presented a systems view that reinforced the importance of partnerships, pathways and progress for creating and sustaining a better-built world; especially for multi-residential, densely populated buildings like those in SJT. No single private or public sector actor can solve problems in isolation, making partnerships a must.

He also encouraged stakeholders to look outside the box of traditional commercial building approaches including how Passive House and NetZero practices might be applied.

As an example, he referenced a Passive House retrofit in Hamilton, a rooftop solar panels project, block power, heat pump and solar PV retrofits and tenant engagement projects in New York State, and a Social Value Portal in the UK.

All in all, building developers and investors need to be encouraged and reassured that sustainability will ultimately have a positive effect on rates of return.

Bala Gnanam, Vice President Sustainability, Advocacy & Stakeholder RelationsBuilding Owners and Managers Association of Canada (BOMA Canada)

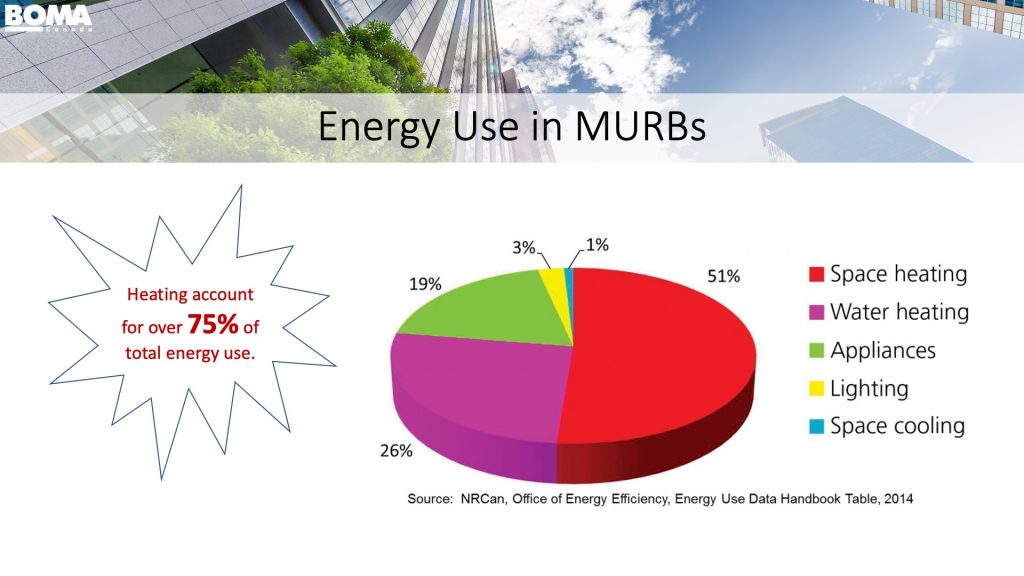

Bala talked about the importance of performance management with a focus on managing emissions. Using the analogy of a three-legged stool, sustainable buildings need three elements: technical improvements, a sustainability-focused organization and occupants who are aware and involved. He also spoke about saving resources like energy and water – the former being a huge chunk of a building’s impact, and therefore a huge opportunity for improvement.

Understand the difference between Emergency Response Plan and Resilience Plan. Although these two are related they serve different business functions. An emergency response plan is very procedural (how to respond to risks) and designed to preserve health and safety. Whereas the resilience plan aims to maintain or restore key business/operational functions through measures to mitigate risks. We need to understand the risks unique to each building and then create an action plan for both emergencies and resiliency.

For buildings, it is sustainability and performance that enable their ability to recover after a shock – the resilience. It is critical to understand the operational conditions and requirements of buildings and then develop strategies and plans to systematically address performance at each site.

Kevin Smith, Ph.D., Technical University of Denmark, Researcher

As a Canadian living in Denmark, Dr. Smith shared examples of energy-efficient buildings and communities that could inspire Canadians.

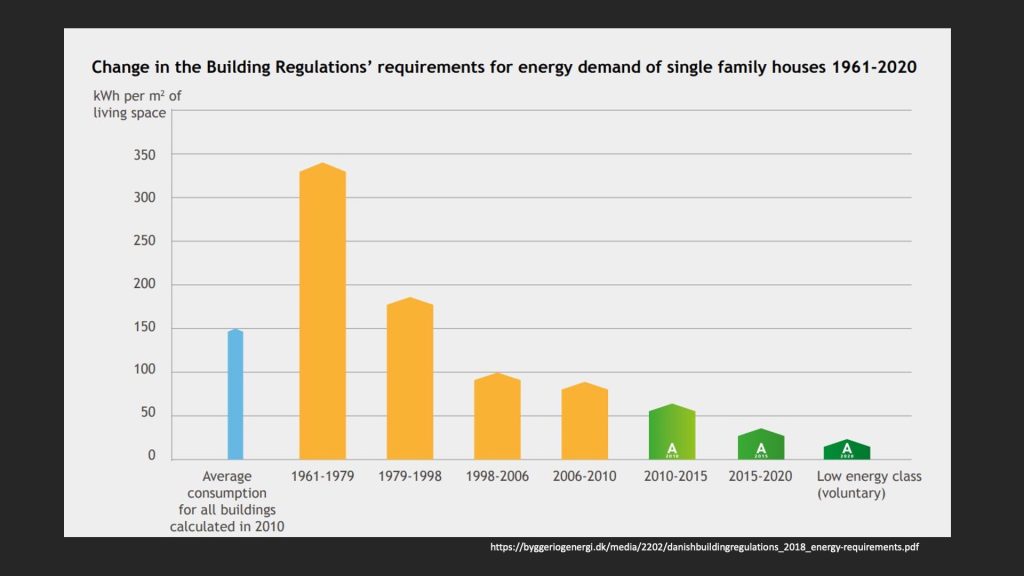

Kevin explained how 54% of Danish buildings came to rely on cost-effective, resilient district heating networks to meet their heating needs. Since the OPEC oil crisis, Denmark has delivered excess heat from power plants burning fossil fuels, municipal waste, and wood pellets/chips to local neighbourhoods while scrubbing their emissions. They also saved energy by implementing strict building regulations, country-wide cycling infrastructure and top-class public transit. As Denmark transitions to carbon neutrality, they are replacing their power plants with generation from renewable energy sources such as wind, solar, and geothermal.

Kevin described how heat pumps are essential in this transition, and their use in Denmark has increased by 92% in the past five years. Heat pumps use electricity to efficiently move heat from lower temperature heat sources, like the ground or sewage, to higher temperature heat sinks, like a building’s heating system. He highlighted the improved costs, reliability and efficiency of district- and building-level heating and cooling systems using heat pumps and recommended coordinated action to plan and realize these systems.

Lastly, Kevin described the importance of renovating buildings to reduce heat loss through leaks and windows before investing in heat pumps to maintain low costs while emphasizing the importance of reliable ventilation to avoid mold and poor air quality.

Q&A with the Speakers

Where is the starting point to have local governments move forward?

Focusing on regulations, standards, incentives and research and development. Funding for these programs is already in place, it’s a matter of motiving action by building owners. Owners and investors are critical in this process, and a key component for motivating change will be asking them what they would like their legacy to be.

People often talk about climate change at a high level, but how do we communicate that at an easier level for people who own the buildings?

Climate change is difficult to grasp conceptually and we must link it to building owners’ experiences, what they can see day-to-day. We need to focus on these direct experiences and not high-level overviews.

With everything that is in place, very little is happening — what can we do about that?

We need to focus on regulations, standards, incentives, occupant engagement and partnerships. In Denmark, for example, “rent control” is used: building owners who make their buildings more energy-efficient are able to charge higher rent. Ultimately, we should start reframing the issue from problems to solutions.

Panel Discussion

Nigel Etherington, P.Eng., Planet & Company, President

Nigel is a senior Toronto- based ESG executive and management consultant serving clients in Canada and abroad. He co-founded Planet & Company as a sustainability-focused advisory. P&C focuses on incorporating strategy, innovation, risk mitigation and continuous improvements with clients in corporate, governmental and NGO sectors. Their mission is to co-create and accelerate the execution of strategies with triple bottom line benefits: economic, environmental, and social – with a particular focus on enabling energy transition to net-zero.

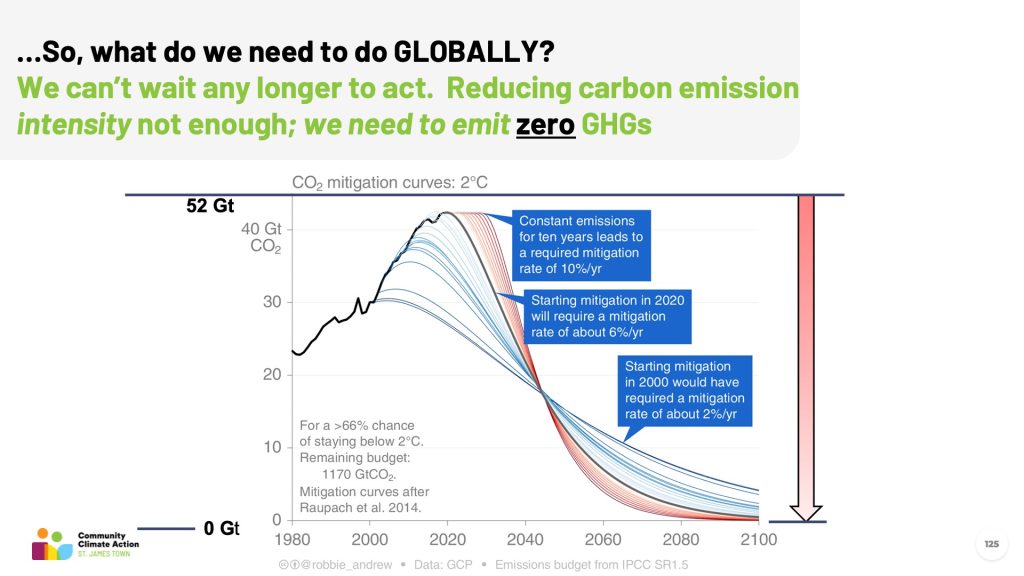

Nigel’s talk on climate change centred around the fact that most of our emissions come from how we manufacture, second only to how we use power. During the global lockdown due to the COVID-19 pandemic, emissions had dropped by 5 percent globally. It is also important to note that, in an effort to reach Net-Zero emissions by the year 2050, we would need to drop global emissions from 52 Gigatons per year to ZERO! To reach zero (0) Gigatons, this is equivalent to having a global “pandemic-like” lockdown that increases every year till 2050 by 6 percent annually! That is why this could be mankind’s greatest challenge.

Q&A with the Panelists

How could you see these Climate Change solutions being implemented if tenant bills tripled?

Ultimately, government regulations would need to drive things and it would need to be a top-down approach with additional funding to help support tenants. Penalties for landlords who don’t address climate would be essential; at the same time, increased prices would be difficult for tenants to manage, so government funding and support would be necessary.

Is heating included in your rent or a separate charge?

Heating is typically included; however, it is still not sufficient. Tenants often require additional heating appliances, increasing energy consumption. If people feel no incentive to protect the planet, we have to create a cost reduction incentive to make them care.

How can these solutions be realized?

It really comes down to funding. We would need to inject money into buildings in order to have them be more energy efficient. We would need to focus on the building envelope and ensure that it is energy efficient in order to reduce energy waste, thus reducing the overall cost. This cannot be a continuous patch job on each of the buildings, it should be fixed at its foundation going forward. Again, this all comes down to regulation and financing.

How would building owners engage with the city in order to move forward with these climate change solutions?

We would need to focus on a primary motivation. It would also be good to reframe the issue from being a problem to being an opportunity. Stakeholders need to have some skin in the game to feel more invested in making a difference.

Is there an incentive for a carbon tax?

Unless things are economically equivalent, society will naturally move towards a lower-cost solution. In terms of progress, it doesn’t seem that economics and these proposed solutions are moving fast enough to mitigate the impacts of climate change. We need to step up our standards. As a point of interest, Toronto’s Green Standard only applies to new construction, leaving a gap for older buildings.

Do the politicians need more courage or is it up to the tenants and community?

The real concern is that tenants will need to foot the bill in terms of upgrades and changes. It is really up to the political change-makers to develop more courage in order to move society toward addressing climate change.

Key Takeaways

- The transition away from fossil fuels as energy will be humanity’s hardest task ever.

- All levels of government can only do so much, and individuals must take responsibility and be more willing to act collectively and effectively to eliminate greenhouse gas emissions.

- No single private or public sector actor has the resources or capabilities to achieve these changes alone; we must work as one.

- Resilience planning is an important step in our effort to mitigate operational, financial and legal risks, and protect the value of investment for building owners and shareholders.

- There is much more to building performance than energy efficiency.

- It is essential that tenants, owners, investors and governments engage proactively, constructively and systemically to improve physical and social resilience.

- Governments and communities must plan and develop energy systems that rely on heat pumps and local renewable energy sources to maximize cost-benefit and resilience.

- Building owners and investors must improve building envelopes and reduce the temperature requirements of water-based heating and cooling systems to enable a cost-effective transition.